KIERKEGAARD, SØREN.

Herman H. J. Lynge & Søn A/S

lyn62110

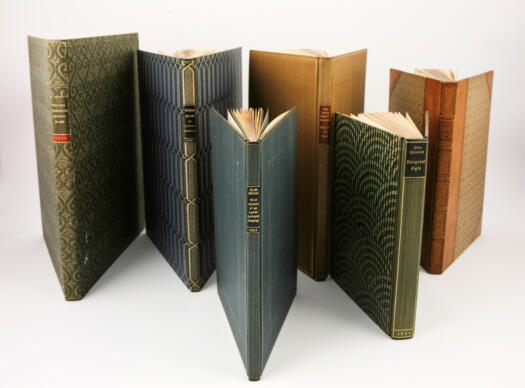

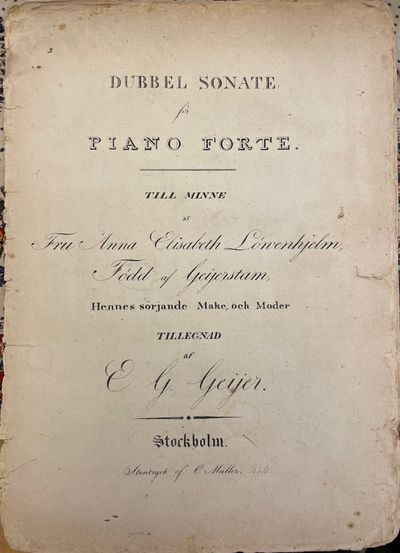

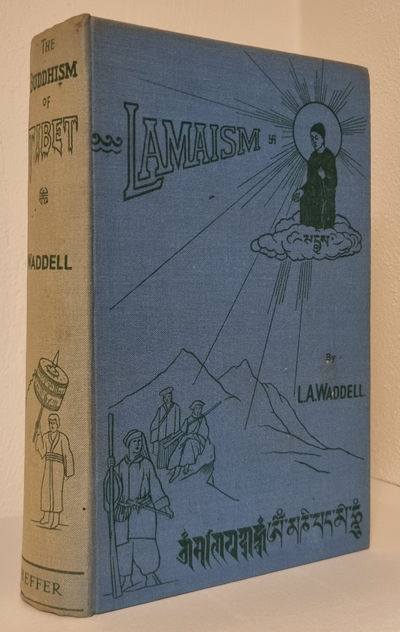

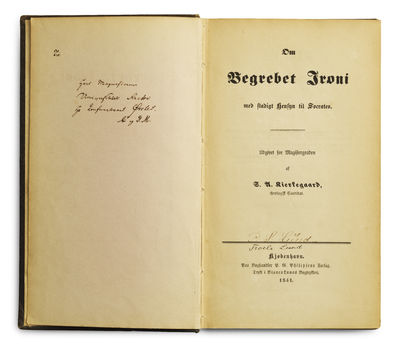

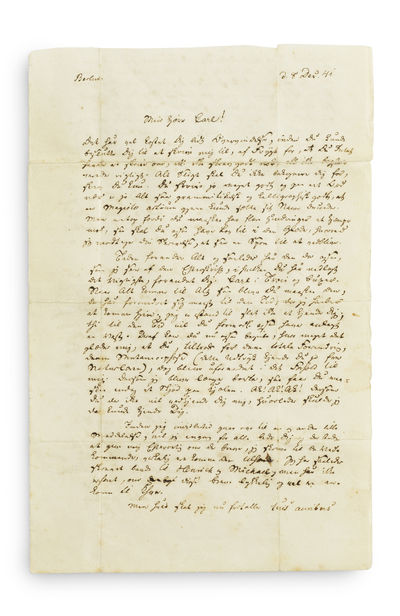

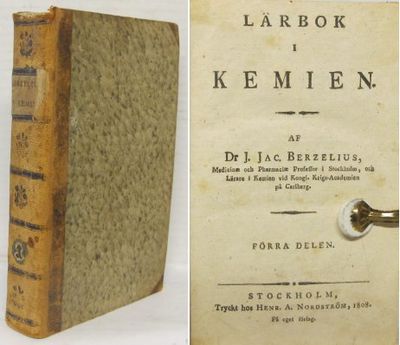

Kjøbenhavn, P.G. Philipsens Forlag, 1841. 8vo. (8), 350 pp. Gift binding of elaborately blindpatterned full cloth with single gilt lines to spine. All edges gilt and printed on thick vellum paper. A splendid copy in completely unrestored state with minimal edge wear. Slight sunning to upper 1 cm of front board and slight bumping to corners and capitals. Leaves completely fresh and clean. Pencil-annotation from the Kierkegaard archive of the Royal Library (nr. 83) and discreet stamp from the Royal Library of Copenhagen to inside of front board (with a deaccession-inscription) and to verso of title-page. With ownership signatures of P.S. Lund and Troels Lund to title-page. Inside of back board with previous owner’s pencil-annotations listing the entire provenance of the copy and explaining that this is one of two copies printed on thick vellum paper. Laid in is the original agreement for the exchange of real property between the previous owner and the Royal Library of Denmark, from which is evident that in 2003, The Royal Library and the previous owner legally agreed to exchange their respective copies of Om Begrebet Ironie – the present one for Ørsted, being one of two copies on thick vellum paper, and the copy on normal paper for Heiberg, which is now in the holdings of the Royal Library of Denmark. Arguably the best possible copy one can ever hope to acquire of Kierkegaard’s dissertation – one of two copies on thick vellum paper, being a presentation-copy from Kierkegaard to the discoverer of electromagnetism H.C. Ørsted. Inscribed to verso of front fly-leaf: “Til / Hans Magnificens / Universitetets Rector / Hr. Conferentsraad Ørsted. / C og D.M.” (For / His Magnificence / Principle of the University / Mr. [a high Danish title, now obsolete] Ørsted. / C (ommandør) (i.e. Commander) and DM (short for Dannebrogsmand, another honourable title) ). The copy is with the Thesis, and both the day and the time has been filled in by hand. As mentioned in the introduction to the Irony, Kierkegaard had two copies made on thick vellum paper –one for himself (which is in the Royal Library of Denmark), and one for H. C. Ørsted, a towering figure of the Danish Golden Age, one of the most important scientists that Denmark has produced, then principle of the University of Copenhagen. This copy is unique among the 11 registered presentation-copies of Kierkegaard’s dissertation and is without doubt the most desirable. It is approximately twice as thick as the other copies and stand out completely. THIS IS KIERKEGAARD’S dissertation, which constitutes the culmination of three years’ intensive studies of Socrates and “the true point of departure for Kierkegaard’s authorship” (Brandes). The work is of the utmost importance in Kierkegaard’s production, not only as his first academic treatise, but also because he here introduces several themes that will be addressed in his later works. Among these we find the question of defining the subject of cognition and self-knowledge of the subject. The maxim of “know thyself” will be a constant throughout his oeuvre, as is the theory of knowledge acquisition that he deals with here. The dissertation is also noteworthy in referencing many of Hegel’s theses in a not negative context, something that Kierkegaard himself would later note with disappointment and characterize as an early, uncritical use of Hegel. Another noteworthy feature is the fact that the thesis is written in Danish, which was unheard of at the time. Kierkegaard felt that Danish was a more suitable language for the thesis and hadto petition the King to be granted permission to submit it in Danish rather than Latin. This in itself poses as certain irony, as the young Kierkegaard was known to express himself poorly and very long-winded in written Danish. One of Kierkegaard’s only true friends, his school friend H.P. Holst recounts (in 1869) how the two had a special school friendship and working relationship, in which Kierkegaard wrote Latin compositions for Holst, while Holst wrote Danish compositions for Kierkegaard, who “expressed himself in a hopelessly Latin Danish crawling with participial phrases and extraordinarily complicatedsentences” (Garff, p. 139). When Kierkegaard, in 1838, was ready to publish his famous piece on Hans Christian Andersen (see nr. 1 & 2 above), which was to appear in Heiberg’s journal Perseus, Heiberg had agreed to publish the piece, although he had some severe critical comments about the way and the form in which it was written – if it were to appear in Perseus, Heiberg demanded, at the very least, the young Kierkegaard would have to submit it in a reasonably readable Danish. “Kierkegaard therefore turned to his old schoolmate H. P. Holst and asked him to do something with the language…” (Garff, p. 139). From their school days, Holst was well aware of the problem with Kierkegaard’s Danish, and he recounts that over the summer, he actually “translated” Kierkegaard’s article on Andersen into proper Danish. The oral defense was conducted in Latin, however. The judges all agreed that the work submitted was both intelligent and noteworthy. But they were concerned about its style, which was found to be both tasteless, long-winded, and idiosyncratic. We already here witness Kierkegaard’s idiosyncratic approach to content and style that is so characteristic for all of his greatest works. Both stylistically and thematically, Kierkegaard’s and especially a clear precursor for his magnum opus Either-Or that is to be his next publication. The year 1841 is a momentous one in Kierkegaard’s life. It is the year that he completes his dissertation and commences his sojourn in Berlin, but it is also the defining year in his personal life, namely the year that he breaks off his engagement with Regine Olsen. And finally, it is the year that he begins writing Either-Or. In many ways, Either-Or is born directly out of The Concept of Irony and is the work that brings the theory of Irony to life. Part One of the dissertation concentrates on Socrates as interpreted by Xenophon, Plato, and Aristophanes, with a word on Hegel and Hegelian categories. Part Two is a more synoptic discussion of the concept of irony in Kierkegaard’s categories, with examples from other philosophers. The work constitutes Kierkegaard’s attempt at understanding the role of irony in disrupting society, and with Socrates understood through Kierkegaard, we witness a whole new way of interpreting the world before us. Wisdom is not necessarily fixed, and we ought to use Socratic ignorance to approach the world without the inherited bias of our cultures. With irony, we will be able to embrace the not knowing. We need to question the world knowing we may not find an answer. The moment we stop questioning and just accept the easy answers, we succumb to ignorance. We must use irony to laugh at ourselves in order to improve ourselves and to laugh at society in order to improve the world. The work was submitted to the Philosophical Faculty at the University of Copenhagen on June 3rd 1841. Kierkegaard had asked for his dissertation to be ready from the printer’s in ample time for him to defend it before the new semester commenced. This presumably because he had already planned his sojourn to Berlin to hear the master philosopher Schelling. On September 16th, the book was issued, and on September 29th, the defense would take place. The entire defense, including a two hour long lunch break, took seven hours, during which ”an unusually full auditorium” would listen to the official opponents F.C. Sibbern and P.O. Brøndsted as well as the seven “ex auditorio” opponents F.C. Petersen, J.L. Heiberg, P.C. Kierkegaard, Fr. Beck, F.P.J. Dahl, H .J.Thue og C.F. Christens, not to mention Kierkegaard himself. Two weeks later, on October 12th, Kierkegaard broke off his engagement with Regine Olsen (for the implications of this event, see the section about Regine in vol. II). The work appeared in two states – one with the four pages of “Theses”, for academics of the university, whereas the copies without the theses were intended for ordinary sale. These sales copies also do not have “Udgivet for Magistergraden” and “theologisk Candidat” on the title-page. The first page of the theses always contains the day “XXIX” of September written in hand, and sometimes the time “hora X” is also written in hand, but not always. In all, 11 presentation-copies of the dissertation are known, and of these only one is signed (that for Holst), all the others merely state the title and name of the recipient. As is evident from the auction catalogue of his collection, Kierkegaard had a number of copies of his dissertation in his possession when he died. Five of them were bound, and two of them were “nit. M. Guldsnit” (i.e. daintily bound and with gilt edges). These two copies were obviously meant as presentation-copies that he then never gave away. The gift copies of the dissertation were given two types of bindings, both brownish cloth, one type patterned, the other one plain, and some of them have gilt edges, but most of the plain ones do not. There exist two copies on thick vellum paper – one being Kierkegaard’s own copy, the other being the copy for H.C. Ørsted, discoverer of electromagnetism and then principle of the University of Copenhagen. “As already implied, two works of the authorship stand out in the sense that Kierkegaard sent his presentation-copies to a special circle of people: The dissertation from 1841...” (Posselt, Textspejle, p. 91, translated from Danish). Most of the copies were given to former teachers and especially to people who, due to leading positions, personified the university. “For this circle of initiated we can now, due to registered copies, confirm that Kierkegaard gave copies with handwritten dedications to the headmaster of the University H.C. Ørsted (printed on thick paper), Kolderup-Rosenvinge and to J.L. Heiberg. It is granted that Sibbern, Madvig and F.C. Petersen were also given the dissertation as a gift,... but these copies are not known (yet).” (Posselt, Textspejle, pp. 93-94, translated fromDanish). (N.b. We have since handled the copy given to Petersen and can thus confirm that it exists). The presentation-inscriptions in the 11 registered copies of the Irony all follow a certain, strict pattern. “The wording could not be briefer. In the donation of his academic treatise, the otherwise prolific Kierkegaard sticks to name, titles, and the modes of address that goes with the titles.” (Tekstspejle p. 96, translated from Danish). When presenting his later books, he always signs himself “from the author”, sometimes abbreviated (i.e. “Forf.” In stead of “Forfatteren”), unless he is mentioned by name on the title-page as the publisher, not the author, as is the case with some of the pseudonymous works. In that case he signs his inscriptions “From the publisher”, always accompanied by “in deep reverence”, “with reverence”, “with friendship” or the like, adapted to the rank of the recipient and his place on Kierkegaard’s personal scale. An academic treatise, however, published before the oral defense took place – in the mind of Kierkegaard – required certain demands in relation to the donation of it. Thus, the brevity and rigidity in the following inscriptions. With the exception of Kierkegaard Hans Christian Ørsted (1777-1851) is arguably the most famous and influential Dane ever to have lived, universally known for his discovery of Electro-magnetism in 1820, which led to new theories and discoveries that constituted the foundation of all later electro-technology. After this milestone of scientific discovery, Ørsted went on to write a number of important philosophical works on natural philosophy and empiricism, of which The Spirit in Nature is the most famous and the work he himself considered his main work. Both H.C. Andersen and Søren Kierkegaard admit to having been influenced by the writings of Ørsted. “He was an enthusiastic follower of the “Naturphilosophie” school in Germany, whose main object was the unification of physical forces, thus producing a monistic theory of the universe. It was to further this purpose that Oersted sought in actual phenomena the electro-magnetic identity of which he had already convinced himself on metaphysical grounds” (Percy H. Muir in Printing and The Mind of Man). “The natural scientist Hans Christian Ørsted was one of the most significant and influential personalities of his age and together with the sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen, the poet Hans Christian Andersen, and the thinker Søren Kierkegaard, constituted the small handful of figures from “The Danish Golden Age” who achieved international and even world fame.” (Troelsen in Kierkegaard and his Danish Contemporaries I: p. (215) ). In intellectual circles in Denmark at the time of Kierkegaard, Ørsted was inevitable. He influenced not only natural sciences profoundly, but also philosophy, literature, and Danish languages (coining more than 2.000 neologisms). He was furthermore rector of the university of Copenhagen, when Kierkegaard in 1841 submitted his master’s thesis On the Concept of Irony. Being the rector, Ørsted was the one who needed to pass the treatise, but having read it, he was simply not sure whether to do so or not and needed to consult other experts, before making his decision. He ended up allowing it to pass, but not without having first famously said about it (in a letter to Sibbern) that it “makes a generally unpleasant impression on me, particularly because of two things both of which I detest: verbosity and affectation.” (Kirmmmse (edt.): Encounters with Kierkegaard, p. 32). Kierkegaard makes several references to Ørsted’s Spirit in Nature and mentions him several times in his journals and notebooks. Although being of different generations and not particularly close on a personal level, the two intellectual giants would naturally be unavoidably connected in one way or the other. Ørsted was simply so centrally placed and so influential that there was no way around him for someone like Kierkegaard. Himmelstrup 8 The present copy is no. 9 in Girsel's "Kierkegaard" (The Catalogue) which can be found here.

Se hele beskrivelsen