DARWIN, CHARLES.

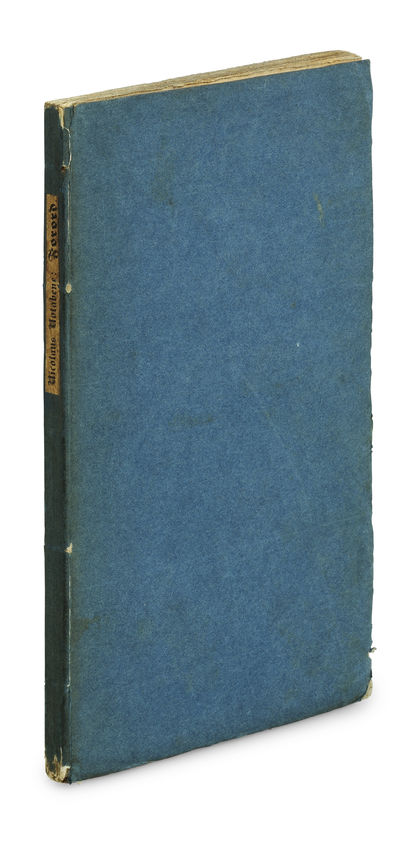

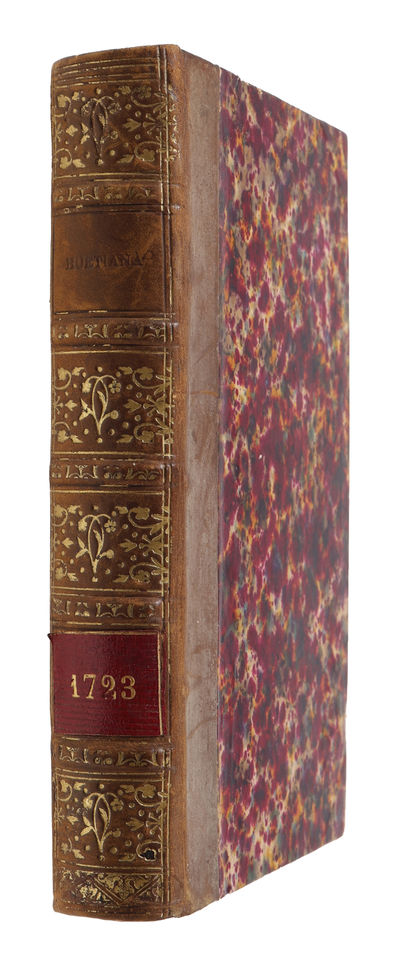

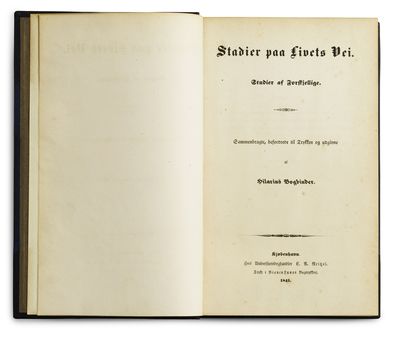

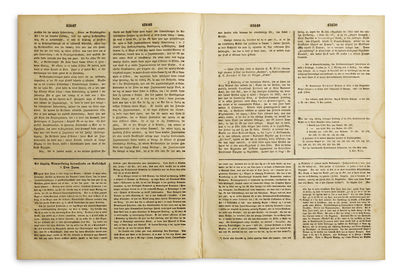

Jinsoron (i.e. Japanese "On the Ancestor(s) of Man", Translated by Kozu Senzaburo, original title: "Descent of Man"). 3 vols. - [FIRST TRANSLATION OF DARWIN INTO JAPANESE]

Herman H. J. Lynge & Søn A/S

lyn60016

Tokyo, Ichibe Yamanaka., Meiji 14. (1881). 8vo. 3 volumes, all in the contemporary (original?) yellow wrappers (Traditional Fukuro Toji binding/wrappers). Extremities with wear and with light soiling, promarily affecting vol. 1. Title in brush and ink to text-block foot. A few ex-ownership stamps. Folding plate with repair. A fine set. 46 ff; 70 ff. + 9 plates of which 1 is folded; 72 ff. "Vol. I contains prefaces to 1st and 2d editions of Descent of man Nos 936 & 944; vol. II contains chapter 1 and vol. III chapter 2. All published, intended to form 9 vols containing chapters 1-7 and 21." (Darwin-Online).

The exceedingly rare first translation of Darwin's Descent of Man and the first (partial) translation of Origin of Species, constituting the very first translation of any of Darwin's work into Japanese and, arguably, being the most influential - albeit in a different way than could be expected - of all Darwin-translations. "The first translation of a book by Darwin was published in 1881: a translation of The Descent of Man, titled as Jinsoron (On the Ancestor(s) of Man; Darwin 1881). The translator was a scholar of education, Kozu Senzaburo (...). In spite of its title, the book was actually a hybrid, which included a mixture of chapters of the Descent (namely, chapters 1-7 and 21) together with other texts: the Historical Sketch that Darwin appended to the third edition of the Origin (1861), and some sections taken from Thomas Huxley's Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature (Kaneko 2000). So this book can also be described as the first publication including a partial translation of a text from the Origin" (Taizo, Translating "natural selection" in Japanese: from "shizen tota" to "shizen sentaku", and back?)Darwin's theories had a profound influence on Japan and Japanese culture but in a slightly different way than in the West: Darwinism was marked as social and political principles primarily embraced by social thinkers, philosophers and politicians to advocate the superiority of Japanese culture and society (and military) and not by biologist and zoologist. "It was as if Darwin's famous oceanic journey and the meticulous research into the animal and plant kingdoms that he spent his life undertaking had all been staged as an elaborate excuse for composing a theory whose true object was Victorian society and the fate of the world's modern nations." (Golley, Darwinism in Japan: The Birth of Ecology).The popularity of Darwin's works and theories became immensly popular in Japan: "Curiously, there are more versions of "The Origin" in Japanese than in any other language. The earliest were literary, with subsequent translations becoming more scientific as the Japanese developed a technical language for biology." (Glick, The Comparatice Reception of Darwinism, P. XXII)Darwin's work had in Japan - as in the rest of the world - profound influence on the academic disciplines of zoology and biology, however, in Japan the most immediate influence was not on these subjects but on social thinkers: "[...] it exerted great influence on Japanese social thinkers and social activists. After learning of Darwin's theory, Hiroyuki Kato, the first president of Tokyo Imperial University, published his New Theory of Human Rights and advocated social evolution theory (social Darwinism), emphasizing the inevitable struggle for existence in human society. He criticized the burgeoning Freedom and People's right movement. Conversely Siusui Kautoku, a socialist and Japanese translator of the Communist Manifesto, wrote articles on Darwinism, such as "Darwin and Marx" (1904). In this and other articles, he criticized kato's theory on Social Darwinism, insisting that Darwinism does not contradict socialism. The well known anarchist, Sakae Osugi published the third translation of On the Origin of Species in 1914, and later his translation of peter Kropotokin's Mutial Aid: A Factor of Evolution. Osugi spread the idea of mutual aid as the philosophical base of Anarcho-syndicalism." (Tsuyoshi, The Japanese Lysenkoism and its Historical Backgrounds, p. 9) "Charles Darwin's theory of evolution was introduced to Japan in 1877 (Morse 1936/1877) during Japan's push to gain military modernity through study of western sciences and technologies and the culture from which they had arisen. In the ensuing decades the theory of evolution was applied as a kind of social scientific tool, i.e. social Spencerism (or social Darwinism) (Sakura 1998:341; Unoura 1999). Sakura (1998) suggests that the theory of evolution did not have much biological application in Japan. Instead, Japanese applied the idea of 'the survival of the fittest' (which was a misreading of Darwin's natural selection theory) to society and to individuals in the struggle for existence in Japan's new international circumstances (see also Gluck 1985: 13, 265).However, at least by the second decade of the 1900s, and by the time that Imanishi Kinji entered the Kyoto Imperial University, the curricula in the natural and earth sciences were largely based on German language sources and later on English language texts. These exposed students to something very different from a social Darwinist approach in these sciences. New sources that allow us to follow" (ASQUITH, Sources for Imanishi Kinji's views of sociality and evolutionary outcomes, p. 1)."After 1895, the year of China's defeat in the Sino-Japanese War, Spencer's slogan "the survival of the fittest" entered Chinese and Japanese writings as "the superior win, the inferior lose." Concerned with evolutionary theory in terms of the survival of China, rather than the origin of species, Chinese intellectuals saw the issue as a complex problem involving the evolution of institutions, ideas, and attitudes. Indeed, they concluded that the secret source of Western power and the rise of Japan was their mutual belief in modern science and the theory of evolutionary progress. According to Japanese scholars, traditional Japanese culture was not congenial to Weastern science because the Japanese view of the relationship between the human world and the divine world was totally different from that of Western philosophers. Japanese philosophers envisioned a harmonious relationship between heaven and earth, rather than conflict. Traditionally, nature was something to be seen through the eyes of a poet, rather than as the passive object of scientific investigations. The traditional Japanese vision of harmony in nature might have been uncongenial to a theory based on natural selection, but Darwinism was eagerly adopted by Japanese thinkers, who saw it as a scientific retionalization for Japan's intense efforts to become a modernized military and industial power. Whereas European and American scientists and theologians became embroiled in disputes about the evolutionary relationship between humans and other animals, Japanese debates about the meaning of Darwinism primarily dealt with the national and international implications of natural selection and the struggle for survival. Late nineteenth-century Japanese commentators were likely to refer to Darwinism as an "eternal and unchangeable natural law" that justified militaristic nationalism directed by supposedly superior elites". (Magner, A History of the Life Sciences, Revised and Expanded, p. 349)"Between 1877 and 1888, only four works on the subject of biological evolution were published in Japan. During these same eleven years, by contrast, at least twenty Japanese translations of Herbert Spencer's loosely "Darwinian" social theories made their appearance. The social sciences dominated the subject, and when Darwin's original The Origin of Species (Seibutsu shigen) finally appeared in translation in 1896, it was published by a press specializing in economics. It is not surprising then that by the early 20th century, when Darwin's work began to make an impact as a biological rather than a "social" theory, the terms "evolution" (shinka), "the struggle for existence" (seizon kyôsô), and "survival of the fittest" (tekisha seizon) had been indelibly marked as social and political principles. It was as if Darwin's famous oceanic journey and the meticulous research into the animal and plant kingdoms that he spent his life undertaking had all been staged as an elaborate excuse for composing a theory whose true object was Victorian society and the fate of the world's modern nations." (Golley, Darwinism in Japan: The Birth of Ecology).Freeman 1099c

The exceedingly rare first translation of Darwin's Descent of Man and the first (partial) translation of Origin of Species, constituting the very first translation of any of Darwin's work into Japanese and, arguably, being the most influential - albeit in a different way than could be expected - of all Darwin-translations. "The first translation of a book by Darwin was published in 1881: a translation of The Descent of Man, titled as Jinsoron (On the Ancestor(s) of Man; Darwin 1881). The translator was a scholar of education, Kozu Senzaburo (...). In spite of its title, the book was actually a hybrid, which included a mixture of chapters of the Descent (namely, chapters 1-7 and 21) together with other texts: the Historical Sketch that Darwin appended to the third edition of the Origin (1861), and some sections taken from Thomas Huxley's Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature (Kaneko 2000). So this book can also be described as the first publication including a partial translation of a text from the Origin" (Taizo, Translating "natural selection" in Japanese: from "shizen tota" to "shizen sentaku", and back?)Darwin's theories had a profound influence on Japan and Japanese culture but in a slightly different way than in the West: Darwinism was marked as social and political principles primarily embraced by social thinkers, philosophers and politicians to advocate the superiority of Japanese culture and society (and military) and not by biologist and zoologist. "It was as if Darwin's famous oceanic journey and the meticulous research into the animal and plant kingdoms that he spent his life undertaking had all been staged as an elaborate excuse for composing a theory whose true object was Victorian society and the fate of the world's modern nations." (Golley, Darwinism in Japan: The Birth of Ecology).The popularity of Darwin's works and theories became immensly popular in Japan: "Curiously, there are more versions of "The Origin" in Japanese than in any other language. The earliest were literary, with subsequent translations becoming more scientific as the Japanese developed a technical language for biology." (Glick, The Comparatice Reception of Darwinism, P. XXII)Darwin's work had in Japan - as in the rest of the world - profound influence on the academic disciplines of zoology and biology, however, in Japan the most immediate influence was not on these subjects but on social thinkers: "[...] it exerted great influence on Japanese social thinkers and social activists. After learning of Darwin's theory, Hiroyuki Kato, the first president of Tokyo Imperial University, published his New Theory of Human Rights and advocated social evolution theory (social Darwinism), emphasizing the inevitable struggle for existence in human society. He criticized the burgeoning Freedom and People's right movement. Conversely Siusui Kautoku, a socialist and Japanese translator of the Communist Manifesto, wrote articles on Darwinism, such as "Darwin and Marx" (1904). In this and other articles, he criticized kato's theory on Social Darwinism, insisting that Darwinism does not contradict socialism. The well known anarchist, Sakae Osugi published the third translation of On the Origin of Species in 1914, and later his translation of peter Kropotokin's Mutial Aid: A Factor of Evolution. Osugi spread the idea of mutual aid as the philosophical base of Anarcho-syndicalism." (Tsuyoshi, The Japanese Lysenkoism and its Historical Backgrounds, p. 9) "Charles Darwin's theory of evolution was introduced to Japan in 1877 (Morse 1936/1877) during Japan's push to gain military modernity through study of western sciences and technologies and the culture from which they had arisen. In the ensuing decades the theory of evolution was applied as a kind of social scientific tool, i.e. social Spencerism (or social Darwinism) (Sakura 1998:341; Unoura 1999). Sakura (1998) suggests that the theory of evolution did not have much biological application in Japan. Instead, Japanese applied the idea of 'the survival of the fittest' (which was a misreading of Darwin's natural selection theory) to society and to individuals in the struggle for existence in Japan's new international circumstances (see also Gluck 1985: 13, 265).However, at least by the second decade of the 1900s, and by the time that Imanishi Kinji entered the Kyoto Imperial University, the curricula in the natural and earth sciences were largely based on German language sources and later on English language texts. These exposed students to something very different from a social Darwinist approach in these sciences. New sources that allow us to follow" (ASQUITH, Sources for Imanishi Kinji's views of sociality and evolutionary outcomes, p. 1)."After 1895, the year of China's defeat in the Sino-Japanese War, Spencer's slogan "the survival of the fittest" entered Chinese and Japanese writings as "the superior win, the inferior lose." Concerned with evolutionary theory in terms of the survival of China, rather than the origin of species, Chinese intellectuals saw the issue as a complex problem involving the evolution of institutions, ideas, and attitudes. Indeed, they concluded that the secret source of Western power and the rise of Japan was their mutual belief in modern science and the theory of evolutionary progress. According to Japanese scholars, traditional Japanese culture was not congenial to Weastern science because the Japanese view of the relationship between the human world and the divine world was totally different from that of Western philosophers. Japanese philosophers envisioned a harmonious relationship between heaven and earth, rather than conflict. Traditionally, nature was something to be seen through the eyes of a poet, rather than as the passive object of scientific investigations. The traditional Japanese vision of harmony in nature might have been uncongenial to a theory based on natural selection, but Darwinism was eagerly adopted by Japanese thinkers, who saw it as a scientific retionalization for Japan's intense efforts to become a modernized military and industial power. Whereas European and American scientists and theologians became embroiled in disputes about the evolutionary relationship between humans and other animals, Japanese debates about the meaning of Darwinism primarily dealt with the national and international implications of natural selection and the struggle for survival. Late nineteenth-century Japanese commentators were likely to refer to Darwinism as an "eternal and unchangeable natural law" that justified militaristic nationalism directed by supposedly superior elites". (Magner, A History of the Life Sciences, Revised and Expanded, p. 349)"Between 1877 and 1888, only four works on the subject of biological evolution were published in Japan. During these same eleven years, by contrast, at least twenty Japanese translations of Herbert Spencer's loosely "Darwinian" social theories made their appearance. The social sciences dominated the subject, and when Darwin's original The Origin of Species (Seibutsu shigen) finally appeared in translation in 1896, it was published by a press specializing in economics. It is not surprising then that by the early 20th century, when Darwin's work began to make an impact as a biological rather than a "social" theory, the terms "evolution" (shinka), "the struggle for existence" (seizon kyôsô), and "survival of the fittest" (tekisha seizon) had been indelibly marked as social and political principles. It was as if Darwin's famous oceanic journey and the meticulous research into the animal and plant kingdoms that he spent his life undertaking had all been staged as an elaborate excuse for composing a theory whose true object was Victorian society and the fate of the world's modern nations." (Golley, Darwinism in Japan: The Birth of Ecology).Freeman 1099c

Adress:

Silkegade 11

DK-1113 Copenhagen Denmark

Telefon:

CVR/VAT:

DK 16 89 50 16

E-post:

Webb:

![Jinsoron (i.e. Japanese "On the Ancestor(s) of Man", Translated by Kozu Senzaburo, original title: "Descent of Man"). 3 vols. - [FIRST TRANSLATION OF DARWIN INTO JAPANESE] (photo 1)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/042/119/1429119042.0.l.jpg)

![Jinsoron (i.e. Japanese "On the Ancestor(s) of Man", Translated by Kozu Senzaburo, original title: "Descent of Man"). 3 vols. - [FIRST TRANSLATION OF DARWIN INTO JAPANESE] (photo 2)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/042/119/1429119042.1.l.0.jpg)

![Jinsoron (i.e. Japanese "On the Ancestor(s) of Man", Translated by Kozu Senzaburo, original title: "Descent of Man"). 3 vols. - [FIRST TRANSLATION OF DARWIN INTO JAPANESE] (photo 3)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/042/119/1429119042.2.l.0.jpg)

![Jinsoron (i.e. Japanese "On the Ancestor(s) of Man", Translated by Kozu Senzaburo, original title: "Descent of Man"). 3 vols. - [FIRST TRANSLATION OF DARWIN INTO JAPANESE] (photo 4)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/042/119/1429119042.3.l.0.jpg)

![Jinsoron (i.e. Japanese "On the Ancestor(s) of Man", Translated by Kozu Senzaburo, original title: "Descent of Man"). 3 vols. - [FIRST TRANSLATION OF DARWIN INTO JAPANESE] (photo 5)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/042/119/1429119042.4.l.0.jpg)

![Jinsoron (i.e. Japanese "On the Ancestor(s) of Man", Translated by Kozu Senzaburo, original title: "Descent of Man"). 3 vols. - [FIRST TRANSLATION OF DARWIN INTO JAPANESE] (photo 6)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/042/119/1429119042.5.l.0.jpg)

![Jinsoron (i.e. Japanese "On the Ancestor(s) of Man", Translated by Kozu Senzaburo, original title: "Descent of Man"). 3 vols. - [FIRST TRANSLATION OF DARWIN INTO JAPANESE] (photo 7)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/042/119/1429119042.6.l.0.jpg)

![Jinsoron (i.e. Japanese "On the Ancestor(s) of Man", Translated by Kozu Senzaburo, original title: "Descent of Man"). 3 vols. - [FIRST TRANSLATION OF DARWIN INTO JAPANESE] (photo 8)](https://d3525k1ryd2155.cloudfront.net/h/042/119/1429119042.7.l.0.jpg)